In the mid-1970s I was a student at Amherst College. Although there were many ways that Amherst was substantially imperfect, there were also many ways in which Amherst created a strong, healthy and inclusive sense of community. This is a story about allies and community.

At Amherst, a pretty large segment of the black students had jobs on campus. Many of these students, myself included, were attending Amherst on financial aid and these on-campus jobs were either part of our financial aid agreement or simply essential to our ability to make ends meet. The most popular jobs on campus for black students were in Valentine Dining Hall. These jobs ran the gamut from the relatively cushy meal-ticket takers to the food servers, clearing food from the tables or working in the hot, steamy, nasty dishwashing room. None of the jobs were glamorous, none were easy, but we had a strong sense of community because we were the black students all working together.

Bob Follette was in charge of operations in Valentine and he was very good at his job in a compassionate, student-centered sort of way. Bob was our boss and Bob was the man that made sure that any black student who needed a job would get one. Bob was also very good at looking the other way. Bob looked the other way whenever one of us workers spent more time goofing around and having fun than doing our job. Bob looked the other way whenever a student brought their date from another college to eat in Valentine. If you lived off campus and needed a meal, you were always welcome in Valentine. And Bob looked the other way when an occasional black student who lived off campus would take home a loaf of bread and a quart of milk. Bob cared about our well-being.

Bob was a white man in his forties, with a slight build and a keen fashion sense not to dress like the mid-1970s, even though it was. Bob was the kind of person who would smile at you and actually mean it. And Bob was gay. His partner was a black man who was a librarian in Robert Frost Library on campus. That may be why Bob always showed so much kindness and respect to the rest of us. That may be why we always had nothing but affection and respect for Bob. Bob was not “out” in the sense that we think of it today, but Bob was who he was and it was not a secret to anyone.

I don’t really know the organizational hierarchy in Valentine, but Bob had a boss. As far as anyone could observe, their relationship was fairly laissez faire. And then one day during my junior year, Bob got a new boss. Bob’s new boss did not like him. Didn’t like that he was gay. He came up with some apparently flimsy excuse and fired Bob. The first ones to learn of this were the black students because so many of us worked for Bob. The black students reacted and responded immediately. We had a tremendous loyalty to Bob, but also wondered how new management might treat the rest of us.

Jimmi Williams, Amherst class of ’77 (a year older than me) was one of the black students who worked in Valentine. James “Jimmi” Williams III was a tall, skinny, dark-skinned brother from Greensboro, North Carolina who spoke with an almost falsetto high-pitched voice. Jimmi, with an ever-present smile was about six feet tall and maybe 120 pounds soaking wet. Jimmi was also one of the most likeable students on campus. Jimmi was also a fierce social activist and leading voice among Amherst’s black students. Jimmi’s easy going demeanor and ever-present smile belied his true calling as a fiery and passionate leader among the black students at Amherst. There wasn’t a person of color on that campus at that time who didn’t admire and look up to Jimmi. The school administration knew that when Jimmi spoke, he spoke for all of us. And there was more than one occasion during my time at Amherst where that solidarity was put to the test.

When news reached us that Bob had been fired, Jimmi declared – first among the fellow black student workers and then to the black students all across campus – “They treating Bob like a nigger. We can’t have that. Bob is our brother.”

The decision was made; until Bob Follette got his job back, no one on campus eats. For two days the black students at Amherst launched a workers strike, dining hall sit-in and building occupation. For two days the black students prevented food from being served to anyone. The college was caught completely unprepared. Talks with the administration were hastily called. The negotiations were very simple; give Bob his job back and this would all be over. Since no replacement for Bob had been hired, it was not difficult to give him back his job. The college and Bob’s boss were able to negotiate some face-saving gesture (that had no significant practical impact), and peace was restored.

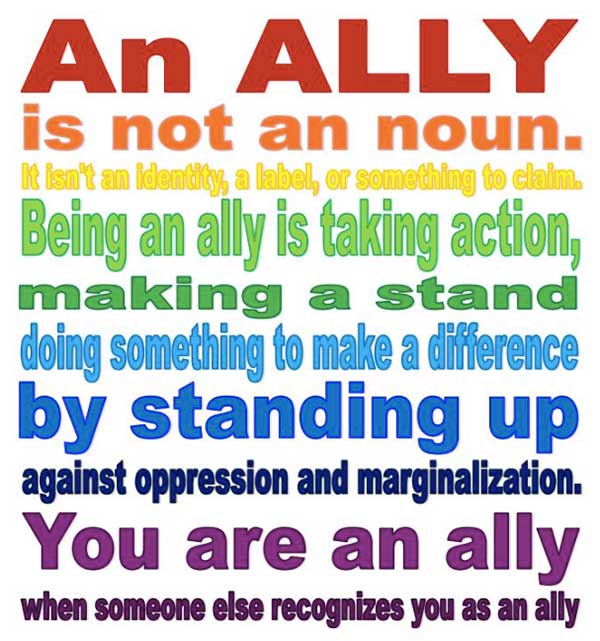

This is what allies do. They care for each other. They fight for each other. They put themselves on the line for each other.