This table shows the full list of our continuously-expanding “Today in “Hidden” History” entries, organized by month, day, and year (i.e., entries that occurred on January 1 will appear in succession, from earliest to latest year, following by entries that occurred on January 2, etc.). We invite readers to submit suggestions for entries by clicking our Contact Us link.

| Date | Type | Event |

|---|---|---|

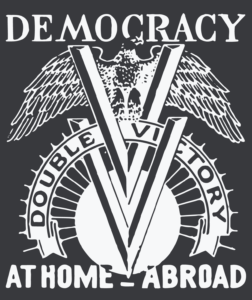

| January 31, 1942 |  The Pittsburgh Courier, then the largest Black newspaper in the United States and a champion for civil rights, publishes a letter from twenty-six-year-old James Thompson a defense worker. As a Black man, Thompson was prohibited from working on the factory floor of the aircraft manufacturing company where he was employed. Thompson’s letter challenged the lofty rhetoric of American war aims and contrasted them to the actual treatment of African Americans. Thomson called for a “double VV for victory” sign, with the first V standing for victory over enemies outside of the country, and the second V for victory over those in the United States who limited the freedoms of African Americans. The Courier adopted the “Double V” insignia and slogan as a campaign for civil rights. Many historians see the “Double V” campaign as the opening salvo in the Civil Rights Movement and continued protests for racial justice. Learn more. The Pittsburgh Courier, then the largest Black newspaper in the United States and a champion for civil rights, publishes a letter from twenty-six-year-old James Thompson a defense worker. As a Black man, Thompson was prohibited from working on the factory floor of the aircraft manufacturing company where he was employed. Thompson’s letter challenged the lofty rhetoric of American war aims and contrasted them to the actual treatment of African Americans. Thomson called for a “double VV for victory” sign, with the first V standing for victory over enemies outside of the country, and the second V for victory over those in the United States who limited the freedoms of African Americans. The Courier adopted the “Double V” insignia and slogan as a campaign for civil rights. Many historians see the “Double V” campaign as the opening salvo in the Civil Rights Movement and continued protests for racial justice. Learn more. | |

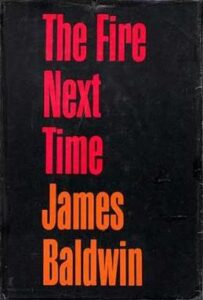

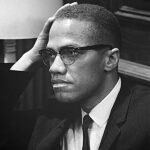

| January 31, 1963 |  James Baldwin publishes The Fire Next Time, a non-fiction book containing two essays: (1) the explosive "Down at the Cross: Letter from a Region of My Mind", that had appeared in The New Yorker in November 1962; and (2) "My Dundgeon Shook: Letter to My Nephew on the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Emancipation". The book addresses racial tensions in America, the role of religion as both an oppressive force and an instrument for inspiring rage, and the necessity of embracing change and evolving past our limited ways of thinking about race. Learn more. James Baldwin publishes The Fire Next Time, a non-fiction book containing two essays: (1) the explosive "Down at the Cross: Letter from a Region of My Mind", that had appeared in The New Yorker in November 1962; and (2) "My Dundgeon Shook: Letter to My Nephew on the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Emancipation". The book addresses racial tensions in America, the role of religion as both an oppressive force and an instrument for inspiring rage, and the necessity of embracing change and evolving past our limited ways of thinking about race. Learn more. | |

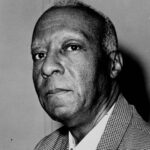

| January 31, 1964 |  Louis Allen is shot twice in the face with a shotgun outside his home in Liberty, Mississippi, dying instantly. A few years before, Allen witnessed a white state legislator murder an NAACP member in cold blood. Mr. Allen was initially intimidated into stating that it was self defense, but later told the FBI it was murder. Because the FBI refused to provide protection to Mr. Allen, he declined to testify. Nonetheless, Mr. Allen was targeted, falsely jailed, and abused by a local sheriff, who was the son of a high-ranking KKK member and a suspected Klan member. The sheriff, who was the main suspect in Mr. Allen's murder, told Allen’s widow, “If Louis had just shut his mouth, he wouldn’t be layin’ there on the ground.” No one has ever been charged or convicted for the murder. Learn more. Louis Allen is shot twice in the face with a shotgun outside his home in Liberty, Mississippi, dying instantly. A few years before, Allen witnessed a white state legislator murder an NAACP member in cold blood. Mr. Allen was initially intimidated into stating that it was self defense, but later told the FBI it was murder. Because the FBI refused to provide protection to Mr. Allen, he declined to testify. Nonetheless, Mr. Allen was targeted, falsely jailed, and abused by a local sheriff, who was the son of a high-ranking KKK member and a suspected Klan member. The sheriff, who was the main suspect in Mr. Allen's murder, told Allen’s widow, “If Louis had just shut his mouth, he wouldn’t be layin’ there on the ground.” No one has ever been charged or convicted for the murder. Learn more. | |

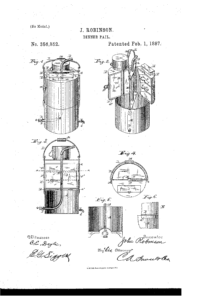

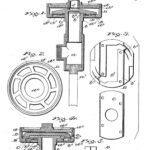

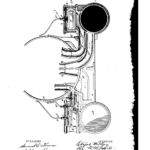

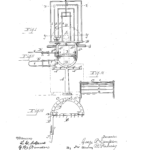

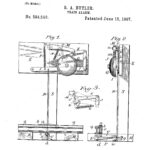

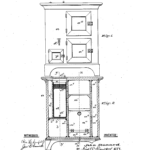

| February 1, 1887 |  John Robinson of Coal Valley, in Fayette County West Virginia, secures US patent # 356852A for his invention of a heatable dinner pail. Learn more. John Robinson of Coal Valley, in Fayette County West Virginia, secures US patent # 356852A for his invention of a heatable dinner pail. Learn more. | |

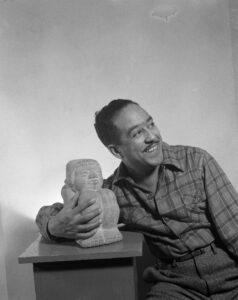

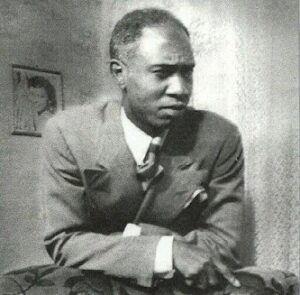

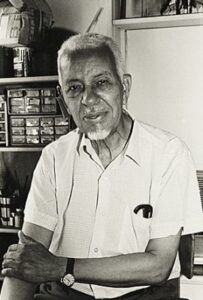

| February 1, 1901 |  Acclaimed American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist Langston Hughes (full name James Mercer Langston Hughes) is born in Joplin, Missouri. One of the earliest innovators of the literary art form called jazz poetry, Hughes is best known as a leader of the Harlem Renaissance. He famously wrote about the period that "the Negro was in vogue", which was later paraphrased as "when Harlem was in vogue." Growing up in a series of Midwestern towns, Hughes became a prolific writer at an early age. He graduated from high school in Cleveland, Ohio, and soon began studies at Columbia University in New York City, where he made his career. Although he dropped out, he gained notice from New York publishers, first in The Crisis magazine, and then from book publishers and became known in the creative community in Harlem. He eventually graduated from Lincoln University. In addition to poetry, Hughes wrote plays, and short stories. He also published several non-fiction works. From 1942 to 1962, as the civil rights movement was gaining traction, he wrote an in-depth weekly column in a leading black newspaper, The Chicago Defender. Learn more. Acclaimed American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist Langston Hughes (full name James Mercer Langston Hughes) is born in Joplin, Missouri. One of the earliest innovators of the literary art form called jazz poetry, Hughes is best known as a leader of the Harlem Renaissance. He famously wrote about the period that "the Negro was in vogue", which was later paraphrased as "when Harlem was in vogue." Growing up in a series of Midwestern towns, Hughes became a prolific writer at an early age. He graduated from high school in Cleveland, Ohio, and soon began studies at Columbia University in New York City, where he made his career. Although he dropped out, he gained notice from New York publishers, first in The Crisis magazine, and then from book publishers and became known in the creative community in Harlem. He eventually graduated from Lincoln University. In addition to poetry, Hughes wrote plays, and short stories. He also published several non-fiction works. From 1942 to 1962, as the civil rights movement was gaining traction, he wrote an in-depth weekly column in a leading black newspaper, The Chicago Defender. Learn more. | |

| February 1, 1960 |  At 4:30 pm, the Greensboro Sit-Ins, a series of nonviolent protests occurring primarily in the Woolworth Store (now the International Civil Rights Center and Museum) in Greensboro, North Carolina, begin when the "Greensboro Four" -- Ezell Blair Jr., David Richmond, Franklin McCain and Joseph McNeil -- are refused service at the store's lunch counter when they each request a cup of coffee. The protests will continue into July of 1960, and lead the F.W. Woolworth Company department store chain to remove its policy of racial segregation in the south. While not the first sit-in of the civil rights movement, the Greensboro sit-ins were an instrumental action, and also the best-known sit-ins of the civil rights movement. They are considered a catalyst to the subsequent sit-in movement, in which 70,000 people participated. This sit-in was a contributing factor in the formation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Learn more. At 4:30 pm, the Greensboro Sit-Ins, a series of nonviolent protests occurring primarily in the Woolworth Store (now the International Civil Rights Center and Museum) in Greensboro, North Carolina, begin when the "Greensboro Four" -- Ezell Blair Jr., David Richmond, Franklin McCain and Joseph McNeil -- are refused service at the store's lunch counter when they each request a cup of coffee. The protests will continue into July of 1960, and lead the F.W. Woolworth Company department store chain to remove its policy of racial segregation in the south. While not the first sit-in of the civil rights movement, the Greensboro sit-ins were an instrumental action, and also the best-known sit-ins of the civil rights movement. They are considered a catalyst to the subsequent sit-in movement, in which 70,000 people participated. This sit-in was a contributing factor in the formation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Learn more. | |

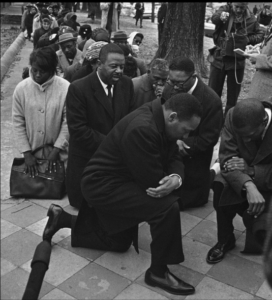

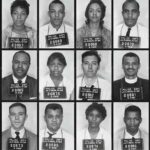

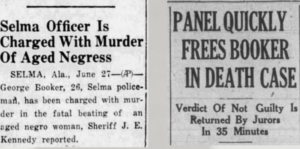

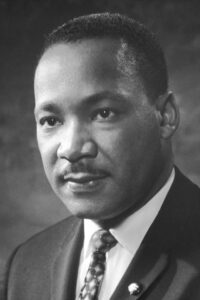

| February 1, 1965 |  Rev., Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. leads more than 250 activists to the Dallas County Courthouse in Selma, Alabama to register to vote. All of them were arrested during the peaceful demonstration and charged with parading without a permit. In a letter written from the local jail that same night, and later published in the New York Times, Dr. King decried the racist conditions in Selma and observed that "there are more Negroes in jail with me than there are on the voting rolls." Dallas County Sheriff Jim Clark, others in local law enforcement, and county registration employees regularly used violence, discrimination, and intimidation to prevent Black residents of Selma from registering to vote. Though African Americans constituted approximately 50% of Selma's population in the 1960s, only 1-2% were registered voters. The arrests of Dr. King and the other civil rights activists resulted in protests in which African Americans were injured and killed. Despite these attacks, Dr. King and other civil rights leaders continued their work and organized another voting rights march from Selma to Montgomery the following month. Learn more. Rev., Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. leads more than 250 activists to the Dallas County Courthouse in Selma, Alabama to register to vote. All of them were arrested during the peaceful demonstration and charged with parading without a permit. In a letter written from the local jail that same night, and later published in the New York Times, Dr. King decried the racist conditions in Selma and observed that "there are more Negroes in jail with me than there are on the voting rolls." Dallas County Sheriff Jim Clark, others in local law enforcement, and county registration employees regularly used violence, discrimination, and intimidation to prevent Black residents of Selma from registering to vote. Though African Americans constituted approximately 50% of Selma's population in the 1960s, only 1-2% were registered voters. The arrests of Dr. King and the other civil rights activists resulted in protests in which African Americans were injured and killed. Despite these attacks, Dr. King and other civil rights leaders continued their work and organized another voting rights march from Selma to Montgomery the following month. Learn more. | |

| February 2, 1897 |  African American businessman and inventor Alfred L. Craile secures U.S. patent # 576,395 for his invention of the ice cream scoop ("Ice Cream Mold and Disher"). Born in 1866 in Virginia, just after the American Civil War, as a young adult Craile later settled in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania where he initially worked as a porter in a drug store and hotel. Noticing that servers at the hotel had trouble with ice cream sticking to serving spoons, Craile developed the ice cream scoop with a built-in scraper to allow for one-handed operation. His design remains in use to this day. He later become a general manager for the Afro-American Financial, Accumulating, Merchandise and Business association. Learn more. African American businessman and inventor Alfred L. Craile secures U.S. patent # 576,395 for his invention of the ice cream scoop ("Ice Cream Mold and Disher"). Born in 1866 in Virginia, just after the American Civil War, as a young adult Craile later settled in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania where he initially worked as a porter in a drug store and hotel. Noticing that servers at the hotel had trouble with ice cream sticking to serving spoons, Craile developed the ice cream scoop with a built-in scraper to allow for one-handed operation. His design remains in use to this day. He later become a general manager for the Afro-American Financial, Accumulating, Merchandise and Business association. Learn more. | |

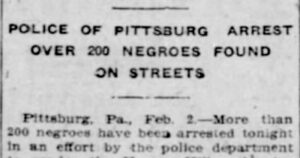

| February 2, 1909 |  Police in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania raid the city’s Herron Hill neighborhood and arrest over 200 Black men for being unemployed. Officers charged Black men with vagrancy if they could not prove their employment status, resulting in mass arrests. The next day, city officials sent the arrested men to the workhouse and consigned them to forced labor. Beginning soon after Emancipation, vagrancy laws were among the discriminatory policies used to criminalize and re-enslave Black people. Though the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified in 1865 and claimed to abolish enslavement in the country, a large loophole allowed this abuse to continue: the amendment’s language prohibited slavery and involuntary servitude, “except as a punishment for crime.” The mass arrests in Pittsburgh are just one example of the way Black people were re-enslaved for decades after the “end” of slavery in America. Learn more. Police in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania raid the city’s Herron Hill neighborhood and arrest over 200 Black men for being unemployed. Officers charged Black men with vagrancy if they could not prove their employment status, resulting in mass arrests. The next day, city officials sent the arrested men to the workhouse and consigned them to forced labor. Beginning soon after Emancipation, vagrancy laws were among the discriminatory policies used to criminalize and re-enslave Black people. Though the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified in 1865 and claimed to abolish enslavement in the country, a large loophole allowed this abuse to continue: the amendment’s language prohibited slavery and involuntary servitude, “except as a punishment for crime.” The mass arrests in Pittsburgh are just one example of the way Black people were re-enslaved for decades after the “end” of slavery in America. Learn more. | |

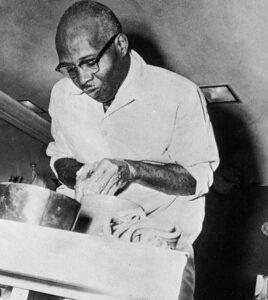

| February 2, 1914 |  African American sculptor William Ellisworth Artis is born in Washington, North Carolina. Ellisworth's favorite medium was clay, which gave him a broad range of expression. He moved to New York as a teen in 1927, and was a pupil of Augusta Savage and exhibited with the Harmon Foundation. He was featured in the 1930s film A Study of Negro Artists, along with Savage and other artists associated with the Harlem Renaissance, including Richmond Barthé, James Latimer Allen, Palmer Hayden, Aaron Douglas, Lois Mailou Jones, and Georgette Seabrooke. Artis taught at the Harlem YMCA, and later served on the faculties of Nebraska State Teachers College, as Professor of Ceramics at Chadron State College and as Professor of Art at Mankato State College. Learn more. African American sculptor William Ellisworth Artis is born in Washington, North Carolina. Ellisworth's favorite medium was clay, which gave him a broad range of expression. He moved to New York as a teen in 1927, and was a pupil of Augusta Savage and exhibited with the Harmon Foundation. He was featured in the 1930s film A Study of Negro Artists, along with Savage and other artists associated with the Harlem Renaissance, including Richmond Barthé, James Latimer Allen, Palmer Hayden, Aaron Douglas, Lois Mailou Jones, and Georgette Seabrooke. Artis taught at the Harlem YMCA, and later served on the faculties of Nebraska State Teachers College, as Professor of Ceramics at Chadron State College and as Professor of Art at Mankato State College. Learn more. | |

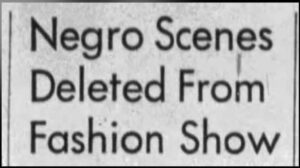

| February 2, 1935 |  Professional ballerina Anne Raven Wilkinson is born in New York City to Anne James Wilkinson and Dr. Frost Bernie Wilkinson, a dentist. Her family, which also included younger brother Frost Bernie Wilkinson, Jr., lived in a middle-class neighborhood in Harlem. In August 1955 at the age of 20, Raven Wilkinson became the first African American woman to receive a contract to dance full time with a major ballet company, the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo of New York City. She was promoted to soloist during her second season with the troupe, and remained with the company for six years. Performing with the company also meant, as Wilkerson soon discovered, touring throughout the U.S., including the still racially-segregated South. Wilkinson had pale skin, and in order to perform with the Company in the South, she was asked not to publicize her race. Additionally Wilkinson often had to wear white makeup onstage to conceal her racial identity. In 1957, the owner of a hotel in Atlanta asked Wilkinson if she was black. When she refused to lie, she was barred from staying at the hotel with the rest of the company. During the same tour, two members of the Ku Klux Klan bolted on stage, interrupting a performance in Montgomery, Alabama, asking “Where’s the nigra?” When none of the Company members responded to them, the men left. Nonetheless, as word of Wilkinson’s racial identity became generally known, she was not allowed to participate in performances in southern cities partly to ensure her own safety. In 1961, Wilkinson left the Ballet Russe Company and was never hired by another American ballet company again. In 1966, Wilkinson got a soloist contract with the Dutch National Ballet, where she stayed for seven years. Learn more. Professional ballerina Anne Raven Wilkinson is born in New York City to Anne James Wilkinson and Dr. Frost Bernie Wilkinson, a dentist. Her family, which also included younger brother Frost Bernie Wilkinson, Jr., lived in a middle-class neighborhood in Harlem. In August 1955 at the age of 20, Raven Wilkinson became the first African American woman to receive a contract to dance full time with a major ballet company, the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo of New York City. She was promoted to soloist during her second season with the troupe, and remained with the company for six years. Performing with the company also meant, as Wilkerson soon discovered, touring throughout the U.S., including the still racially-segregated South. Wilkinson had pale skin, and in order to perform with the Company in the South, she was asked not to publicize her race. Additionally Wilkinson often had to wear white makeup onstage to conceal her racial identity. In 1957, the owner of a hotel in Atlanta asked Wilkinson if she was black. When she refused to lie, she was barred from staying at the hotel with the rest of the company. During the same tour, two members of the Ku Klux Klan bolted on stage, interrupting a performance in Montgomery, Alabama, asking “Where’s the nigra?” When none of the Company members responded to them, the men left. Nonetheless, as word of Wilkinson’s racial identity became generally known, she was not allowed to participate in performances in southern cities partly to ensure her own safety. In 1961, Wilkinson left the Ballet Russe Company and was never hired by another American ballet company again. In 1966, Wilkinson got a soloist contract with the Dutch National Ballet, where she stayed for seven years. Learn more. | |

| February 3, 1943 |  At 12:55 am, the United States troop transport the USAT Dorchester is hit by a torpedo by German U-boat U-233. The troop carrier lists badly and begins to sink rapidly as scores of troops were pitched into the seas. Sailing immediately behind the Dorchester, twelve men from the US Coast Guard cutter Comanche volunteer to rescue men from the frigid waters, including Steward’s Mate First Class Charles Walter David, Jr, one of the lowest-ranking men on the ship. They dive into the waters, putting ropes around men’s waists because most were suffering from hypothermia, and could not grab a rescue line. David rescues ninety-three of the two hundred and twenty-seven survivors, including ranking officer Lt. Robert Anderson. David died of pneumonia on March 29, 1943, fifty-four days after the ordeal, at the age of twenty-six. He was posthumously awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal for Heroism in 1943. This award was followed by the American Defense Service Medal, the American Campaign Medal, the European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal, and the WWII Victory Medal. He was honored with a certificate for his heroism by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1963. The Immortal Chaplains Foundation awarded David with their prestigious Prize for Humanity in 1999, and in 2010, the USCGC Charles David Jr. was named as the seventh new Sentinel Class Cutter in his honor. At 12:55 am, the United States troop transport the USAT Dorchester is hit by a torpedo by German U-boat U-233. The troop carrier lists badly and begins to sink rapidly as scores of troops were pitched into the seas. Sailing immediately behind the Dorchester, twelve men from the US Coast Guard cutter Comanche volunteer to rescue men from the frigid waters, including Steward’s Mate First Class Charles Walter David, Jr, one of the lowest-ranking men on the ship. They dive into the waters, putting ropes around men’s waists because most were suffering from hypothermia, and could not grab a rescue line. David rescues ninety-three of the two hundred and twenty-seven survivors, including ranking officer Lt. Robert Anderson. David died of pneumonia on March 29, 1943, fifty-four days after the ordeal, at the age of twenty-six. He was posthumously awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal for Heroism in 1943. This award was followed by the American Defense Service Medal, the American Campaign Medal, the European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal, and the WWII Victory Medal. He was honored with a certificate for his heroism by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1963. The Immortal Chaplains Foundation awarded David with their prestigious Prize for Humanity in 1999, and in 2010, the USCGC Charles David Jr. was named as the seventh new Sentinel Class Cutter in his honor. | |

| February 3, 1948 |  Rosa Lee Ingram, a Black woman, and two of her children, Wallace, 17, and Sammie Lee, 14, were convicted by an all-white jury in a one-day trial in Ellaville, Georgia and sentenced to death by electric chair for killing an armed white man in self-defense as he violently assaulted them, even though the local Sheriff admitted the sons acted in defense of their mother. The judge subsequently reduced their sentences to life in prison. Ms. Ingram and her sons were sent to the state penitentiary and were each forced to serve more than a decade in prison for daring to defend themselves against a violent, armed assault by a white man. The Ingrams were not released on parole until 1959. Learn more. Rosa Lee Ingram, a Black woman, and two of her children, Wallace, 17, and Sammie Lee, 14, were convicted by an all-white jury in a one-day trial in Ellaville, Georgia and sentenced to death by electric chair for killing an armed white man in self-defense as he violently assaulted them, even though the local Sheriff admitted the sons acted in defense of their mother. The judge subsequently reduced their sentences to life in prison. Ms. Ingram and her sons were sent to the state penitentiary and were each forced to serve more than a decade in prison for daring to defend themselves against a violent, armed assault by a white man. The Ingrams were not released on parole until 1959. Learn more. | |

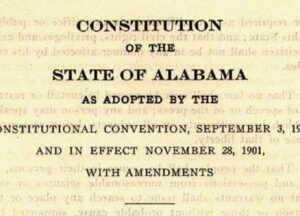

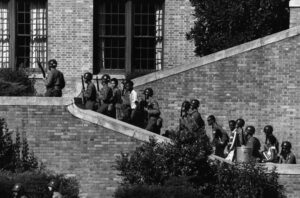

| February 3, 1956 |  Autherine Lucy briefly integrates the University of Alabama. Lucy’s enrollment follows a two-year legal battle she and the NAACP waged to force the University of Alabama to admit Black students. On February 6, Lucy’s 4th day of attendance, a mob of hundreds descend on the university to halt Autherine Lucy’s enrollment. The mob, armed with rocks, eggs, and bricks, scream racist epithets at Lucy and threaten her life, and Lucy is hit in the back with an egg as she was ushered, under police escort, into an auditorium (where she was forced to remain for hours for her own safety). The University of Alabama Board of Trustees suspend Lucy that evening, and later expell her “for her protection and for the protection of other students and staff members.” Her attorneys challenge of the expulsion is unsuccessful. In April 1988, Lucy’s expulsion was overturned, and in spring 1992, she earned a master’s degree in elementary education from the University of Alabama. Learn more. Autherine Lucy briefly integrates the University of Alabama. Lucy’s enrollment follows a two-year legal battle she and the NAACP waged to force the University of Alabama to admit Black students. On February 6, Lucy’s 4th day of attendance, a mob of hundreds descend on the university to halt Autherine Lucy’s enrollment. The mob, armed with rocks, eggs, and bricks, scream racist epithets at Lucy and threaten her life, and Lucy is hit in the back with an egg as she was ushered, under police escort, into an auditorium (where she was forced to remain for hours for her own safety). The University of Alabama Board of Trustees suspend Lucy that evening, and later expell her “for her protection and for the protection of other students and staff members.” Her attorneys challenge of the expulsion is unsuccessful. In April 1988, Lucy’s expulsion was overturned, and in spring 1992, she earned a master’s degree in elementary education from the University of Alabama. Learn more. | |

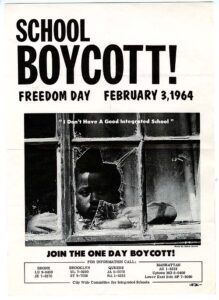

| February 3, 1964 |  The New York City school boycott, known as Freedom Day, takes place in New York City. It is the largest civil rights demonstration of the 1960s and involves nearly half a million Black and Puerto Rican students in a mass boycott and demonstration protesting segregation in the New York City public school system. Students and teachers stayed out of public schools to highlight the deplorable conditions, and demonstrators held rallies demanding integration. Learn more. The New York City school boycott, known as Freedom Day, takes place in New York City. It is the largest civil rights demonstration of the 1960s and involves nearly half a million Black and Puerto Rican students in a mass boycott and demonstration protesting segregation in the New York City public school system. Students and teachers stayed out of public schools to highlight the deplorable conditions, and demonstrators held rallies demanding integration. Learn more. | |

| February 4, 1913 |

| |

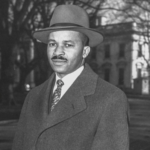

| February 4, 1943 |  Hugh MacBeth, Sr., an African American attorney from Los Angeles, organizer and advocate for west coast Japanese Americans subjected to internment after Pearl Harbor, secures a a writ of habeas corpus from a three-judge panel on behalf of his clients, Ernest and Toki Wakayama. However, by that time the Wakayamas, worn down by large-scale beatings and ostracism at the Manzanar internment camp in Northern California, had withdrawn their suit and requested “repatriation” to Japan, despite the fact that both were born and had lived their entire lives in America. Despite this defeat, MacBeth continued to defend Japanese Americans from segregation, internment, and other racial-drivem injustices. Learn more. Hugh MacBeth, Sr., an African American attorney from Los Angeles, organizer and advocate for west coast Japanese Americans subjected to internment after Pearl Harbor, secures a a writ of habeas corpus from a three-judge panel on behalf of his clients, Ernest and Toki Wakayama. However, by that time the Wakayamas, worn down by large-scale beatings and ostracism at the Manzanar internment camp in Northern California, had withdrawn their suit and requested “repatriation” to Japan, despite the fact that both were born and had lived their entire lives in America. Despite this defeat, MacBeth continued to defend Japanese Americans from segregation, internment, and other racial-drivem injustices. Learn more. | |

| February 4, 1999 |  At 12:40 am, four plainclothes New York City police officers exit their vehicle and approach Amadou Diallo, a Guinean immigrant, while he is in the vestibule of his building. While it is unclear if they identified themselves as police officers, they nontheless sought to question Diallo who in turn did not respond to their request but instead reached into his back pocket. One of the officers yelled “gun,” and all four officers began to shoot at Diallo. A total of forty-one shots were fired from the officers’ weapons. Nineteen shots hit Diallo’s body, and he was killed instantly. Neighbors called 911 after the shooting, and the attending officers called in the incident on their radios. Once other officers arrived on the scene, an investigation began. It was discovered that there was no gun and all that was lying next to Diallo’s body were a pager and a wallet. The shooting catalyzed protests in the city of New York because many believed the officers had acted without restraint. All four officers were indicted, but acquitted. The Diallo killing would be the first of a series of high-profile police killings of Black people that would over a decade later spark the Black Lives Matter movement. Learn more. At 12:40 am, four plainclothes New York City police officers exit their vehicle and approach Amadou Diallo, a Guinean immigrant, while he is in the vestibule of his building. While it is unclear if they identified themselves as police officers, they nontheless sought to question Diallo who in turn did not respond to their request but instead reached into his back pocket. One of the officers yelled “gun,” and all four officers began to shoot at Diallo. A total of forty-one shots were fired from the officers’ weapons. Nineteen shots hit Diallo’s body, and he was killed instantly. Neighbors called 911 after the shooting, and the attending officers called in the incident on their radios. Once other officers arrived on the scene, an investigation began. It was discovered that there was no gun and all that was lying next to Diallo’s body were a pager and a wallet. The shooting catalyzed protests in the city of New York because many believed the officers had acted without restraint. All four officers were indicted, but acquitted. The Diallo killing would be the first of a series of high-profile police killings of Black people that would over a decade later spark the Black Lives Matter movement. Learn more. | |

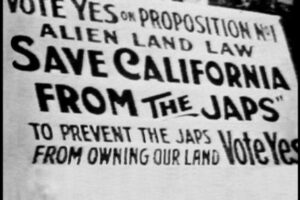

| February 5, 1917 |  Congress passes the Immigration Act of 1917, also known as the Asiatic Barred Zone Act. Intended to prevent “undesirables” from immigrating to the U.S., the act primarily targeted individuals migrating from Asia. Under the act, people from “any country not owned by the United States adjacent to the continent of Asia” were barred from immigrating to the U.S. The bill was not meant to impact immigrants from Northern and Western Europe but targeted Asian, Mexican, and Mediterranean immigrants. The bill remained law for 35 years, until the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1952 eliminated racial restrictions in immigration and naturalization statutes. Learn more. Congress passes the Immigration Act of 1917, also known as the Asiatic Barred Zone Act. Intended to prevent “undesirables” from immigrating to the U.S., the act primarily targeted individuals migrating from Asia. Under the act, people from “any country not owned by the United States adjacent to the continent of Asia” were barred from immigrating to the U.S. The bill was not meant to impact immigrants from Northern and Western Europe but targeted Asian, Mexican, and Mediterranean immigrants. The bill remained law for 35 years, until the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1952 eliminated racial restrictions in immigration and naturalization statutes. Learn more. | |

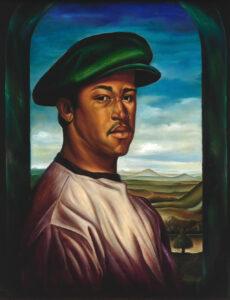

| February 5, 1917 |  Frederick C. Flemister, an artist most recognized for his paintings during the early 1940s, while he was based in Atlanta, Georgia, is born in Jackson, Georgia. He was one of the foremost artists to emerge from a group taught and influenced by Hale Aspacio Woodruff (1900-1980), founder of Atlanta University’s School of Art. Flemister’s most famous paintings include works such as “Self Portrait” (1941), “Man with a Brush,” “The Mourners,” and “Madonna,” were all produced between 1939 and 1945. Though he emerged during the 1940s, his works are often associated with the Harlem Renaissance artists of the 1920s. His style has been described as expressionistic and is often compared to that of 16th-century Italian Renaissance painters. His professor Hale Woodruff was a major artistic influence. Another was El Greco (1541-1614). Flemister’s work has been featured in several exhibits including the High Art Museum in Atlanta, Dillard University, New Orleans; the American Negro Exposition, Chicago; the Institute of Modern Art in Boston; the Albany Institute of History and Art; City College of New York; Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio; and the Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Massachusetts. In February 1944 his work was featured as part of “The Negro in Art” exhibition at the Barnett-Aden Gallery, Washington, D.C. Learn more. Frederick C. Flemister, an artist most recognized for his paintings during the early 1940s, while he was based in Atlanta, Georgia, is born in Jackson, Georgia. He was one of the foremost artists to emerge from a group taught and influenced by Hale Aspacio Woodruff (1900-1980), founder of Atlanta University’s School of Art. Flemister’s most famous paintings include works such as “Self Portrait” (1941), “Man with a Brush,” “The Mourners,” and “Madonna,” were all produced between 1939 and 1945. Though he emerged during the 1940s, his works are often associated with the Harlem Renaissance artists of the 1920s. His style has been described as expressionistic and is often compared to that of 16th-century Italian Renaissance painters. His professor Hale Woodruff was a major artistic influence. Another was El Greco (1541-1614). Flemister’s work has been featured in several exhibits including the High Art Museum in Atlanta, Dillard University, New Orleans; the American Negro Exposition, Chicago; the Institute of Modern Art in Boston; the Albany Institute of History and Art; City College of New York; Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio; and the Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Massachusetts. In February 1944 his work was featured as part of “The Negro in Art” exhibition at the Barnett-Aden Gallery, Washington, D.C. Learn more. | |

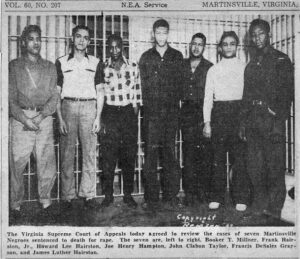

| February 5, 1951 |  The remaining three of the Martinsville Seven are executed by electrocution, the first four having been executed three days before. The Martinsville Seven were a group of young Black men convicted of raping a white woman in Martinsville, VA. On the evening of January 8, 1949, Ruby Stroud Floyd accused 13 black men of raping her while she passed through a poor African American neighborhood in Martinsville, Virginia. The trials and the electrocutions became a cause célèbre similar to the Scottsboro Case of the 1930s. NAACP officials focused national attention to the case, hoping to delay or overturn the death penalty judgment. NAACP lawyers argued on appeal that Virginia’s legal code was hardly race-neutral since whites convicted of rape “seldom if ever” received the death penalty. All appeals were quickly exhausted. Learn more. The remaining three of the Martinsville Seven are executed by electrocution, the first four having been executed three days before. The Martinsville Seven were a group of young Black men convicted of raping a white woman in Martinsville, VA. On the evening of January 8, 1949, Ruby Stroud Floyd accused 13 black men of raping her while she passed through a poor African American neighborhood in Martinsville, Virginia. The trials and the electrocutions became a cause célèbre similar to the Scottsboro Case of the 1930s. NAACP officials focused national attention to the case, hoping to delay or overturn the death penalty judgment. NAACP lawyers argued on appeal that Virginia’s legal code was hardly race-neutral since whites convicted of rape “seldom if ever” received the death penalty. All appeals were quickly exhausted. Learn more. | |

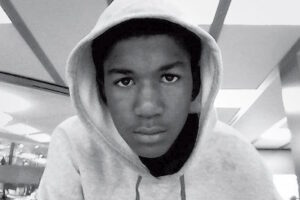

| February 5, 1995 |  Birth of Trayvon Martin, whose tragic death at age 17 in 2012 became the first catalyst for the national Black Lives Matter movement. Learn more. Birth of Trayvon Martin, whose tragic death at age 17 in 2012 became the first catalyst for the national Black Lives Matter movement. Learn more. | |

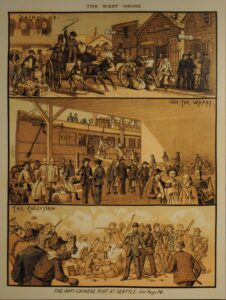

| February 6, 1886 |  The Seattle Riot of 1886 begins in Seattle, Washington when a mob affiliated with a local Knights of Labor chapter forms committees to carry out a forcible expulsion of all Chinese from the city. Violence erupted between the Knights of Labor rioters and federal troops ordered in by President Grover Cleveland over the next two days. The incident resulted in the removal of over 200 Chinese civilians from Seattle and left two militia men and three rioters seriously injured. Learn more. The Seattle Riot of 1886 begins in Seattle, Washington when a mob affiliated with a local Knights of Labor chapter forms committees to carry out a forcible expulsion of all Chinese from the city. Violence erupted between the Knights of Labor rioters and federal troops ordered in by President Grover Cleveland over the next two days. The incident resulted in the removal of over 200 Chinese civilians from Seattle and left two militia men and three rioters seriously injured. Learn more. | |

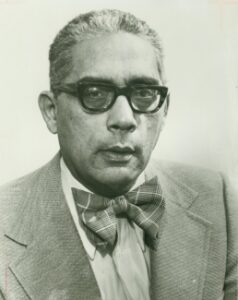

| February 6, 1898 |  Melvin Beaunorus Tolson, educator and one of the most significant African American modernist poets of his time, is born in Moberly, Missouri. Langston Hughes declared him “the most famous Negro Professor in the Southwest” in the mid-twentieth century. After interviewing significant artists of the Harlem Renaissance for his master’s thesis, Tolson was inspired to write poetry exploring the African American urban experience. His poetry began appearing in African American newspapers such as the Washington, D.C. Tribune in the 1930s. Tolson’s first book of poetry, Rendezvous with America, was published in 1944. In the 1970s, Tolson’s poetry was displayed in an exhibit known as “A Gallery of Harlem Portraits” at the University of Virginia. Learn more. Melvin Beaunorus Tolson, educator and one of the most significant African American modernist poets of his time, is born in Moberly, Missouri. Langston Hughes declared him “the most famous Negro Professor in the Southwest” in the mid-twentieth century. After interviewing significant artists of the Harlem Renaissance for his master’s thesis, Tolson was inspired to write poetry exploring the African American urban experience. His poetry began appearing in African American newspapers such as the Washington, D.C. Tribune in the 1930s. Tolson’s first book of poetry, Rendezvous with America, was published in 1944. In the 1970s, Tolson’s poetry was displayed in an exhibit known as “A Gallery of Harlem Portraits” at the University of Virginia. Learn more. | |

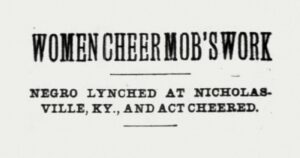

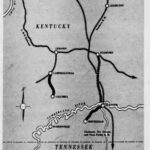

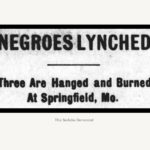

| February 6, 1902 |  A white mob of 200 seizes Thomas Brown, a 19-year-old Black man, from a jail cell and lynches him on the Jessamine County Courthouse lawn in Nicholasville, Kentucky. Thomas had been arrested for an alleged assault on a white woman but never had the chance to stand trial. Though news reports identified the young woman’s brother as a leader of the mob, no one was ever prosecuted for Thomas Brown’s murder and authorities concluded that he "met death by strangulation at the hands of parties unknown." Learn more. A white mob of 200 seizes Thomas Brown, a 19-year-old Black man, from a jail cell and lynches him on the Jessamine County Courthouse lawn in Nicholasville, Kentucky. Thomas had been arrested for an alleged assault on a white woman but never had the chance to stand trial. Though news reports identified the young woman’s brother as a leader of the mob, no one was ever prosecuted for Thomas Brown’s murder and authorities concluded that he "met death by strangulation at the hands of parties unknown." Learn more. | |

| February 6, 1905 |  Merze Tate, a historian, political author, world traveler, philanthropist, and the first African American to graduate from Oxford University is born Blanchard, Michigan. Excelling in her studies, she won an oratorical contest at Battle Creek High School and graduated valedictorian at Blanchard High School. Tate received a scholarship to Western State Teachers College (now Western Michigan University) and became the first African American to graduate, earning a teaching diploma and bachelor’s degree with honors in 1927. In 1935, Tate earned a bachelor of literature degree (B.Litt.) in international relations from Oxford University. She returned home to study political science at Radcliffe College, the prestigious all-female school that later merged with Harvard University. In 1941, she obtained her Ph.D. and was the first Black woman to do so at Radcliffe. In the 1950s, she was a Fulbright Scholar and lecturer for the U.S. Information Agency and visited India, Thailand, Japan, the Philippines, Hong Kong, and Singapore. Learn more. Merze Tate, a historian, political author, world traveler, philanthropist, and the first African American to graduate from Oxford University is born Blanchard, Michigan. Excelling in her studies, she won an oratorical contest at Battle Creek High School and graduated valedictorian at Blanchard High School. Tate received a scholarship to Western State Teachers College (now Western Michigan University) and became the first African American to graduate, earning a teaching diploma and bachelor’s degree with honors in 1927. In 1935, Tate earned a bachelor of literature degree (B.Litt.) in international relations from Oxford University. She returned home to study political science at Radcliffe College, the prestigious all-female school that later merged with Harvard University. In 1941, she obtained her Ph.D. and was the first Black woman to do so at Radcliffe. In the 1950s, she was a Fulbright Scholar and lecturer for the U.S. Information Agency and visited India, Thailand, Japan, the Philippines, Hong Kong, and Singapore. Learn more. | |

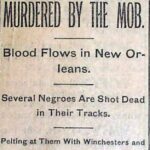

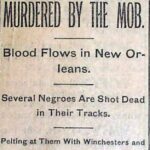

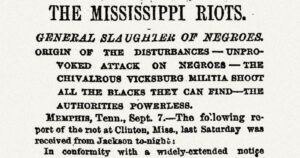

| February 7, 1904 |  As hundreds of white people watched and cheered, a Black man named Luther Holbert and an unidentified Black woman were tortured and killed in Doddsville, Mississippi. As reported in the Vicksburg, Mississippi, Evening Post, the two victims were tied to tree and forced to hold out their hands and watch as their fingers and ears were chopped off, one at a time, and distributed as souvenirs. The mob next bore into the victims' arms, legs, and bodies with a large corkscrew, pulling out large pieces of raw flesh. The victims were finally thrown on a large fire and burned to death. The event was described as a festive atmosphere, in which the audience of 600 spectators enjoyed deviled eggs, lemonade, and whiskey. Learn more. As hundreds of white people watched and cheered, a Black man named Luther Holbert and an unidentified Black woman were tortured and killed in Doddsville, Mississippi. As reported in the Vicksburg, Mississippi, Evening Post, the two victims were tied to tree and forced to hold out their hands and watch as their fingers and ears were chopped off, one at a time, and distributed as souvenirs. The mob next bore into the victims' arms, legs, and bodies with a large corkscrew, pulling out large pieces of raw flesh. The victims were finally thrown on a large fire and burned to death. The event was described as a festive atmosphere, in which the audience of 600 spectators enjoyed deviled eggs, lemonade, and whiskey. Learn more. | |

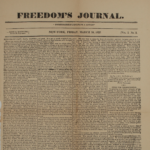

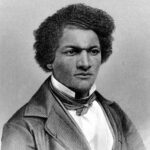

| February 7, 1926 |  The precursor to Black History Month is observed for the first time in the United States, after the historian Carter G. Woodson and the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History announce the second week of February to be "Negro History Week". This week was chosen because it coincided with the birthday of Abraham Lincoln on February 12 and that of Frederick Douglass on February 14, both of which dates Black communities had celebrated together since the late 19th century. At the time of Negro History Week's launch, Woodson contended that the teaching of Black History was essential to ensure the physical and intellectual survival of the race within broader society. In 1976, President Gerald Ford designated the entire month of February as Black History Month. Learn more. The precursor to Black History Month is observed for the first time in the United States, after the historian Carter G. Woodson and the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History announce the second week of February to be "Negro History Week". This week was chosen because it coincided with the birthday of Abraham Lincoln on February 12 and that of Frederick Douglass on February 14, both of which dates Black communities had celebrated together since the late 19th century. At the time of Negro History Week's launch, Woodson contended that the teaching of Black History was essential to ensure the physical and intellectual survival of the race within broader society. In 1976, President Gerald Ford designated the entire month of February as Black History Month. Learn more. | |

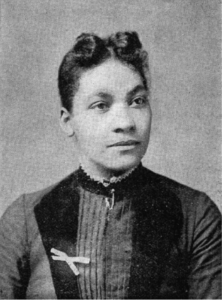

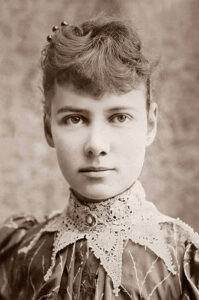

| February 8, 1831 |  Dr. Rebecca Davis Lee Crumpler, the first African American woman doctor in the United States, is born free to Absolum and Matilda (Webber) Davis in Christiana, Delaware. She was raised by an aunt in Pennsylvania who was noted to have provided health care to her neighbors. She completed medical school at the New England Female Medical College and received her M.D. in 1864. Dr. Crumpler first practiced medicine in Boston and specialized in the care of women, children, and the poor. She moved to Richmond, Virginia in 1865 to minister to freedpeople through the Freedmen’s Bureau. Crumpler returned to Boston in 1869, where she practiced from her home on Beacon Hill and dispensed nutritional advice to poor women and children. In 1883, she published a medical guide book, Book of Medical Discourses, which primarily gave advice for women on the health care of their families. Learn more. Dr. Rebecca Davis Lee Crumpler, the first African American woman doctor in the United States, is born free to Absolum and Matilda (Webber) Davis in Christiana, Delaware. She was raised by an aunt in Pennsylvania who was noted to have provided health care to her neighbors. She completed medical school at the New England Female Medical College and received her M.D. in 1864. Dr. Crumpler first practiced medicine in Boston and specialized in the care of women, children, and the poor. She moved to Richmond, Virginia in 1865 to minister to freedpeople through the Freedmen’s Bureau. Crumpler returned to Boston in 1869, where she practiced from her home on Beacon Hill and dispensed nutritional advice to poor women and children. In 1883, she published a medical guide book, Book of Medical Discourses, which primarily gave advice for women on the health care of their families. Learn more.

| |

| February 8, 1902 |  Businesswoman, politician, and civil rights activist, Mae Street Kidd, is born in Millersburg, Kentucky to a Black mother and white father. Kidd’s biological father refused to acknowledge her as his daughter. She attended a segregated Black primary school in her community. As a teenager, Kidd enrolled at Lincoln Institute in Simpsonville, Kentucky, a boarding school for African Americans. She became a successful life insurance agent at the Black owned Mammoth Life Insurance Company. She served in the American Red Cross in England during WWII. Following the war, she became an entrepreneur, opening a cosmetic and an insurance company in the Midwest. Kidd became active in the burgeoning civil rights movement in Louisville. In 1948, she founded the Louisville Urban League Guild. In her sixties, she served in the Kentucky House of Representatives from 1968 to 1984, representing Louisville’s 41st legislative district. Learn more.

Businesswoman, politician, and civil rights activist, Mae Street Kidd, is born in Millersburg, Kentucky to a Black mother and white father. Kidd’s biological father refused to acknowledge her as his daughter. She attended a segregated Black primary school in her community. As a teenager, Kidd enrolled at Lincoln Institute in Simpsonville, Kentucky, a boarding school for African Americans. She became a successful life insurance agent at the Black owned Mammoth Life Insurance Company. She served in the American Red Cross in England during WWII. Following the war, she became an entrepreneur, opening a cosmetic and an insurance company in the Midwest. Kidd became active in the burgeoning civil rights movement in Louisville. In 1948, she founded the Louisville Urban League Guild. In her sixties, she served in the Kentucky House of Representatives from 1968 to 1984, representing Louisville’s 41st legislative district. Learn more. | |

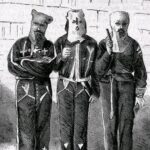

| February 8, 1915 |  The silent epic drama film, The Birth of a Nation, originally called The Clansman, debuts. The film has been called "the most reprehensibly racist film in Hollywood history" and promotes the "Lost Cause" ideology. The film portrays African Americans (many of whom are played by white actors in blackface) as unintelligent and sexually aggressive toward white women. The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) is portrayed as a heroic force, necessary to preserve American values, protect white women, and maintain white supremacy. The film was a huge commercial success and profoundly influenced both the film industry and American culture. The film has been acknowledged as an inspiration for the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan, which took place only a few months after its release. Learn more. The silent epic drama film, The Birth of a Nation, originally called The Clansman, debuts. The film has been called "the most reprehensibly racist film in Hollywood history" and promotes the "Lost Cause" ideology. The film portrays African Americans (many of whom are played by white actors in blackface) as unintelligent and sexually aggressive toward white women. The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) is portrayed as a heroic force, necessary to preserve American values, protect white women, and maintain white supremacy. The film was a huge commercial success and profoundly influenced both the film industry and American culture. The film has been acknowledged as an inspiration for the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan, which took place only a few months after its release. Learn more. | |

| February 8, 1944 |  Harry S. McAlpin becomes the first African American reporter to attend a U.S. Presidential news conference. He is greeted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who shakes his hand and says, "I'm glad to see you, McAlpin, and very happy to have you here." In 1943 the National Negro Publishers Association (NNPA) petitioned the White House Correspondents Association (WHCA) for press credentials on the grounds that the Atlanta Daily World was one of its member papers. All other African American papers at the time were weeklies, and the press credentials were limited to reporters for daily papers. The WHCA agreed but it took several more months before the NNPA could afford to open its own Washington bureau and hire McAlpin as its full-time Washington correspondent. Learn more. Harry S. McAlpin becomes the first African American reporter to attend a U.S. Presidential news conference. He is greeted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who shakes his hand and says, "I'm glad to see you, McAlpin, and very happy to have you here." In 1943 the National Negro Publishers Association (NNPA) petitioned the White House Correspondents Association (WHCA) for press credentials on the grounds that the Atlanta Daily World was one of its member papers. All other African American papers at the time were weeklies, and the press credentials were limited to reporters for daily papers. The WHCA agreed but it took several more months before the NNPA could afford to open its own Washington bureau and hire McAlpin as its full-time Washington correspondent. Learn more. | |

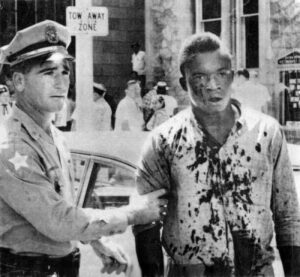

| February 8, 1968 |  On the campus of South Carolina State College, a historically Black college in Orangeburg, South Carolina, white state troopers fire into a large crowd of mostly African Americans protesting segregation in the town. In what became known as the “Orangeburg Massacre,” the troopers shot and wounded 28 people and killed three Black male students: Samuel Hammond, 18, a freshman from Florida; Henry Smith, 18, a sophomore from Marion, South Carolina; and Delano Middleton, 17, an Orangeburg high school student. Witness accounts from reporters, firemen, and students reported that officers had fired on the crowd without warning. No evidence was ever presented that the protesters were armed. None of the nine officers charged for their roles in the shooting were convicted of any wrongdoing, but Cleveland Sellers, program director of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and a protest organizer was convicted of rioting and served seven months in prison. Learn more. On the campus of South Carolina State College, a historically Black college in Orangeburg, South Carolina, white state troopers fire into a large crowd of mostly African Americans protesting segregation in the town. In what became known as the “Orangeburg Massacre,” the troopers shot and wounded 28 people and killed three Black male students: Samuel Hammond, 18, a freshman from Florida; Henry Smith, 18, a sophomore from Marion, South Carolina; and Delano Middleton, 17, an Orangeburg high school student. Witness accounts from reporters, firemen, and students reported that officers had fired on the crowd without warning. No evidence was ever presented that the protesters were armed. None of the nine officers charged for their roles in the shooting were convicted of any wrongdoing, but Cleveland Sellers, program director of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and a protest organizer was convicted of rioting and served seven months in prison. Learn more. | |

| February 9, 1907 |  Charles Alfred Anderson, often called the “Father of Black Aviation,” because of his training and mentoring of hundreds of African American pilots, is born in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, a Philadelphia suburb, to Janie and Iverson Anderson. Charles Anderson earned the name “Chief” because he was the most ranked and experienced African American pilot before coming to Tuskegee Army Air Field (TAAF) in 1940. By that point he had amassed 3,500 hours of flight prompting most of his contemporaries and students to call him by that name as a sign of their respect for his accomplishments. Anderson was also the Chief flight Instructor for all cadets and flight instructors at Tuskegee, Alabama during World War II. Learn more. Charles Alfred Anderson, often called the “Father of Black Aviation,” because of his training and mentoring of hundreds of African American pilots, is born in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, a Philadelphia suburb, to Janie and Iverson Anderson. Charles Anderson earned the name “Chief” because he was the most ranked and experienced African American pilot before coming to Tuskegee Army Air Field (TAAF) in 1940. By that point he had amassed 3,500 hours of flight prompting most of his contemporaries and students to call him by that name as a sign of their respect for his accomplishments. Anderson was also the Chief flight Instructor for all cadets and flight instructors at Tuskegee, Alabama during World War II. Learn more. | |

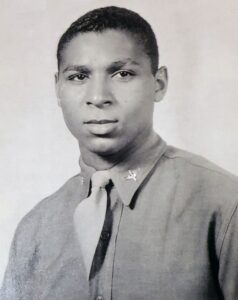

| February 9, 1919 |  Robert Leander Martin, a member of the Tuskegee Airmen, is born in Dubuque, Iowa. Martin became inspired to become a pilot after attending an air show when he was thirteen years old. After graduating from high school, Martin enrolled at Iowa State University in Ames, Iowa. While there he learned to fly in a civilian pilot training program before graduating from the institution in 1942 with a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering. Martin entered the Tuskegee flight training program, the only one the U.S. Army sponsored to train Black pilots for military combat. He graduated from flight training at the Tuskegee Army Airfield as a second lieutenant and soon afterwards was assigned to the 100th Fighter Squadron and the 332nd Fighter Group. During the war, Martin earned the Distinguished Flying Cross, The Air Medal with 6 Oak Leaf Clusters, and the Purple Heart for his heroism. Learn more. Robert Leander Martin, a member of the Tuskegee Airmen, is born in Dubuque, Iowa. Martin became inspired to become a pilot after attending an air show when he was thirteen years old. After graduating from high school, Martin enrolled at Iowa State University in Ames, Iowa. While there he learned to fly in a civilian pilot training program before graduating from the institution in 1942 with a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering. Martin entered the Tuskegee flight training program, the only one the U.S. Army sponsored to train Black pilots for military combat. He graduated from flight training at the Tuskegee Army Airfield as a second lieutenant and soon afterwards was assigned to the 100th Fighter Squadron and the 332nd Fighter Group. During the war, Martin earned the Distinguished Flying Cross, The Air Medal with 6 Oak Leaf Clusters, and the Purple Heart for his heroism. Learn more. | |

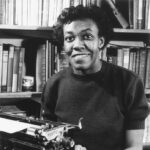

| February 9, 1944 |  Prolific writer, educator, and activist Alice Walker, the first African American to win the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, is born the eighth child of sharecroppers Willie Lee and Minnie Lou Grant Walker in Eatonton, Georgia. Walker became the valedictorian of her segregated high school class, despite an accident at age eight that impaired the vision in her left eye. Before transferring to Sarah Lawrence College, where she received a B.A., she attended Atlanta’s Spelman College for two years, where she became a political activist, met Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and participated in the 1963 March on Washington. Walker later became a major voice in the emerging feminist movement led by mostly white middle-class women. Aware of the issues of race in that movement, Walker later created a specific Black woman centered feminist theory, which she called “womanism,” to identity and assess the oppression based on racism and classism that African American women often experience. Walker’s collected work includes poetry, novels, short fiction, essays, critical essays, and children’s stories. Learn more. Prolific writer, educator, and activist Alice Walker, the first African American to win the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, is born the eighth child of sharecroppers Willie Lee and Minnie Lou Grant Walker in Eatonton, Georgia. Walker became the valedictorian of her segregated high school class, despite an accident at age eight that impaired the vision in her left eye. Before transferring to Sarah Lawrence College, where she received a B.A., she attended Atlanta’s Spelman College for two years, where she became a political activist, met Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and participated in the 1963 March on Washington. Walker later became a major voice in the emerging feminist movement led by mostly white middle-class women. Aware of the issues of race in that movement, Walker later created a specific Black woman centered feminist theory, which she called “womanism,” to identity and assess the oppression based on racism and classism that African American women often experience. Walker’s collected work includes poetry, novels, short fiction, essays, critical essays, and children’s stories. Learn more. | |

| February 9, 1960 |  Just four weeks before her graduation, a bomb exploded at the home of Carlotta Walls, the youngest member of the original “Little Rock Nine," who integrated Little Rock Central High School in 1957. Carlotta, her mother, and her sister were at home when the bomb exploded, but no one was injured. Police arrested and beat Carlotta's father in unsuccessful efforts to coerce a confession. Police then arrested two young Black men, Herbert Monts, a family friend, and Maceo Binns, Jr.; Walls never believed either man was responsible, but both were convicted and sentenced to five years in prison. Three years before, hundreds of white people had attacked Black residents and reporters when the Little Rock Nine entered the high school. In response, segregationist Governor Orville Faubus closed all public high schools in Little Rock for the 1958-1959 school year. Learn more. Just four weeks before her graduation, a bomb exploded at the home of Carlotta Walls, the youngest member of the original “Little Rock Nine," who integrated Little Rock Central High School in 1957. Carlotta, her mother, and her sister were at home when the bomb exploded, but no one was injured. Police arrested and beat Carlotta's father in unsuccessful efforts to coerce a confession. Police then arrested two young Black men, Herbert Monts, a family friend, and Maceo Binns, Jr.; Walls never believed either man was responsible, but both were convicted and sentenced to five years in prison. Three years before, hundreds of white people had attacked Black residents and reporters when the Little Rock Nine entered the high school. In response, segregationist Governor Orville Faubus closed all public high schools in Little Rock for the 1958-1959 school year. Learn more. | |

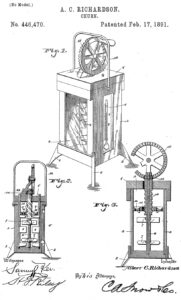

| February 17, 1891 |  African American A.C. Richardson secures US Patent number 446,470 for his invention of an improved butter churn. Learn more. African American A.C. Richardson secures US Patent number 446,470 for his invention of an improved butter churn. Learn more. | |

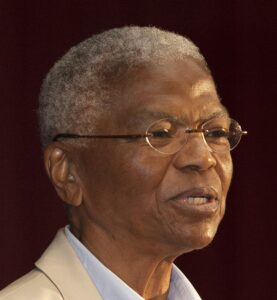

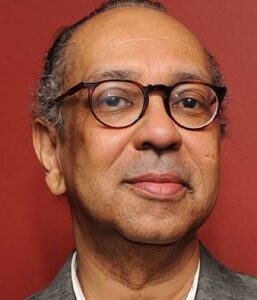

| February 17, 1938 |  Mary Frances Berry, scholar, professor, author, and civil rights activist who served on the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, is born in Nashville, Tennessee to parents Frances Southall Berry and George Ford Berry. Due to her mother’s poverty and the desertion of her father, she and her brothers spent time in an orphanage. She attended the segregated public schools in Nashville but in the 10th grade she found a mentor in her teacher, Minerva Hawkins, who challenged Berry to excel in academics. Berry earned her B.A. in history from Howard University in 1961. She earned a history Ph.D. in 1966 from the University of Michigan. In 1968 Berry became a faculty member at the University of Maryland and supervised the establishment of an African American Studies Program at that institution. Berry earned her law degree from the University of Michigan Law School in 1970 and became the acting director of the Department of Afro-American Studies at the University of Maryland. From 1974 to 1976 she served as University Provost, becoming the first African American woman to hold that position. President Jimmy Carter appointed her to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights in 1980. Her 1993 book The Politics of Parenthood: Child Care, Women’s Rights, and the Myth of the Good Mother, argued for men to take an equal role in child care and for a rethinking of gender roles. In 1993 Berry was appointed Chair of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission by President Bill Clinton and reappointed in 1999. After leaving government in 2004, Berry returned to academia as a professor at the University of Pennsylvania. Learn more.

Mary Frances Berry, scholar, professor, author, and civil rights activist who served on the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, is born in Nashville, Tennessee to parents Frances Southall Berry and George Ford Berry. Due to her mother’s poverty and the desertion of her father, she and her brothers spent time in an orphanage. She attended the segregated public schools in Nashville but in the 10th grade she found a mentor in her teacher, Minerva Hawkins, who challenged Berry to excel in academics. Berry earned her B.A. in history from Howard University in 1961. She earned a history Ph.D. in 1966 from the University of Michigan. In 1968 Berry became a faculty member at the University of Maryland and supervised the establishment of an African American Studies Program at that institution. Berry earned her law degree from the University of Michigan Law School in 1970 and became the acting director of the Department of Afro-American Studies at the University of Maryland. From 1974 to 1976 she served as University Provost, becoming the first African American woman to hold that position. President Jimmy Carter appointed her to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights in 1980. Her 1993 book The Politics of Parenthood: Child Care, Women’s Rights, and the Myth of the Good Mother, argued for men to take an equal role in child care and for a rethinking of gender roles. In 1993 Berry was appointed Chair of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission by President Bill Clinton and reappointed in 1999. After leaving government in 2004, Berry returned to academia as a professor at the University of Pennsylvania. Learn more. | |

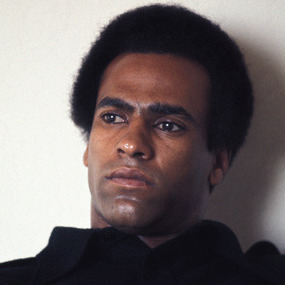

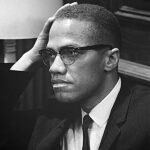

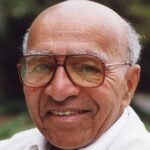

| February 17, 1942 |  Huey P. Newton, cofounder of the Black Panther Party, is born. Despite graduating from high school not knowing how to read, he taught himself literacy by reading Plato's Republic and earned a Ph.D. in social philosophy from the University of California at Santa Cruz's History of Consciousness program in 1980. Newton crafted the Black Panther Party's ten-point manifesto with Bobby Seale in 1966. Under Newton's leadership, the Black Panther Party founded over 60 community support programs (renamed survival programs in 1971) including food banks, medical clinics, sickle cell anemia tests, prison busing for families of inmates, legal advice seminars, clothing banks, housing cooperatives, and their own ambulance service. The most famous of these programs was the Free Breakfast for Children program which fed thousands of impoverished children daily during the early 1970s. Newton also used his position as a leader within the Black Panther Party to welcome women and LGBT people into the party, describing homosexuals as "the most oppressed people" in society.Newton also co-founded the Black Panther newspaper service which became one of America's most widely distributed African-American newspapers. In 1967, he was involved in a shootout which led to the death of a police officer John Frey and injuries to himself and another police officer. In 1968, Newton was convicted of voluntary manslaughter for Frey's death and sentenced to 2 to 15 years in prison, but the conviction was later reversed and after two subsequent trials ended in hung juries, the charges were dropped. Later in life he was also accused of murdering Kathleen Smith and Betty Patter, although he was never convicted for either deaths. In 1989, Newton was murdered in Oakland, California. Learn more. Huey P. Newton, cofounder of the Black Panther Party, is born. Despite graduating from high school not knowing how to read, he taught himself literacy by reading Plato's Republic and earned a Ph.D. in social philosophy from the University of California at Santa Cruz's History of Consciousness program in 1980. Newton crafted the Black Panther Party's ten-point manifesto with Bobby Seale in 1966. Under Newton's leadership, the Black Panther Party founded over 60 community support programs (renamed survival programs in 1971) including food banks, medical clinics, sickle cell anemia tests, prison busing for families of inmates, legal advice seminars, clothing banks, housing cooperatives, and their own ambulance service. The most famous of these programs was the Free Breakfast for Children program which fed thousands of impoverished children daily during the early 1970s. Newton also used his position as a leader within the Black Panther Party to welcome women and LGBT people into the party, describing homosexuals as "the most oppressed people" in society.Newton also co-founded the Black Panther newspaper service which became one of America's most widely distributed African-American newspapers. In 1967, he was involved in a shootout which led to the death of a police officer John Frey and injuries to himself and another police officer. In 1968, Newton was convicted of voluntary manslaughter for Frey's death and sentenced to 2 to 15 years in prison, but the conviction was later reversed and after two subsequent trials ended in hung juries, the charges were dropped. Later in life he was also accused of murdering Kathleen Smith and Betty Patter, although he was never convicted for either deaths. In 1989, Newton was murdered in Oakland, California. Learn more. | |

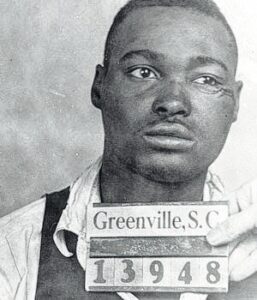

| February 17, 1947 |  Willie Earle, a 24-year-old African American man, was being held in the Pickens County Jail in South Carolina on charges of assaulting a white taxi cab driver. A mob of white men—mostly taxi cab drivers—seized Mr. Earle from the jail, took him to a deserted country road near Greenville, brutally beat him with guns and knives, and then shot him to death. When arrested, 26 of the 31 defendants gave full statements admitting participation in Mr. Earle’s death. The defense did not rebut the confessions, but instead blamed “northern interference” for bringing the case to trial at all. At one point, the defense attorney likened Mr. Earle to a “mad dog” that deserved killing, and the mostly white spectators laughed in support. Despite the undisputed confession, the all-white jury acquitted the defendants of all charges on May 21, 1947, and the judge ordered them released. Learn more. Willie Earle, a 24-year-old African American man, was being held in the Pickens County Jail in South Carolina on charges of assaulting a white taxi cab driver. A mob of white men—mostly taxi cab drivers—seized Mr. Earle from the jail, took him to a deserted country road near Greenville, brutally beat him with guns and knives, and then shot him to death. When arrested, 26 of the 31 defendants gave full statements admitting participation in Mr. Earle’s death. The defense did not rebut the confessions, but instead blamed “northern interference” for bringing the case to trial at all. At one point, the defense attorney likened Mr. Earle to a “mad dog” that deserved killing, and the mostly white spectators laughed in support. Despite the undisputed confession, the all-white jury acquitted the defendants of all charges on May 21, 1947, and the judge ordered them released. Learn more. | |

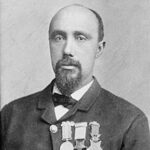

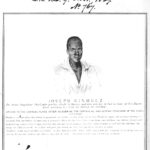

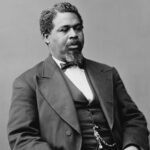

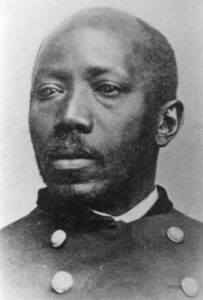

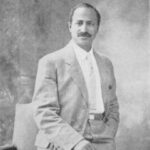

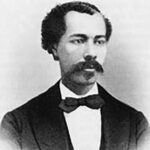

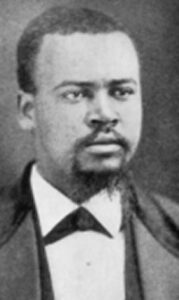

| February 26, 1844 |  Birthday of James E. O’Hara, educator, Howard University law school graduate, practicing attorney admitted to the North Carolina bar, member of the North Carolina House of Representatives in 1868-1869, and only African American member of Congress in 1883, during the 48th Congress. O’Hara was born a free man in New York City to an Irish American father and West Indian mother, settling in North Carolina as a young man. He served two terms in congress before losing re-election in 1886. He died on September 15, 1905 in New Bern, North Carolina at age 61. Learn more. Birthday of James E. O’Hara, educator, Howard University law school graduate, practicing attorney admitted to the North Carolina bar, member of the North Carolina House of Representatives in 1868-1869, and only African American member of Congress in 1883, during the 48th Congress. O’Hara was born a free man in New York City to an Irish American father and West Indian mother, settling in North Carolina as a young man. He served two terms in congress before losing re-election in 1886. He died on September 15, 1905 in New Bern, North Carolina at age 61. Learn more.

| |

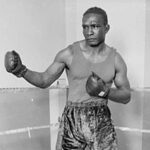

| February 26, 1926 |  Theodore “Tiger” Flowers, nicknamed the “Georgia Deacon,” becomes the first Black middleweight boxing champion. Learn more. Theodore “Tiger” Flowers, nicknamed the “Georgia Deacon,” becomes the first Black middleweight boxing champion. Learn more. | |

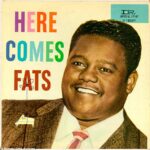

| February 26, 1928 |  Birthday of American pianist, singer-songwriter, and pioneering rock-and-roller, Antoine Dominique “Fats” Domino Jr., whose music sold more than 65 million records. Though little known today, music historians cite his 1949 recording of “The Fat Man” as the first true rock song; it was also the first recording to sell over 1M copies. Elvis Presley called Domino “the real king of rock and roll”. Domino also set the pattern for later rock and pop acts by writing his own music, rather than merely covering songs written by other composers. Learn more.

Birthday of American pianist, singer-songwriter, and pioneering rock-and-roller, Antoine Dominique “Fats” Domino Jr., whose music sold more than 65 million records. Though little known today, music historians cite his 1949 recording of “The Fat Man” as the first true rock song; it was also the first recording to sell over 1M copies. Elvis Presley called Domino “the real king of rock and roll”. Domino also set the pattern for later rock and pop acts by writing his own music, rather than merely covering songs written by other composers. Learn more. | |

| February 27, 1902 |  Birthday of renowned contralto opera singer Marian Anderson, an important figure in the struggle against racial prejudice. She was at the center of an international news story in 1939, when the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) refused to allow Anderson to sing to an integrated audience in Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C. With the aid of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Anderson performed a critically acclaimed open-air concert on Easter Sunday, April 9, 1939, on the Lincoln Memorial steps in the capital. She sang before an integrated crowd of more than 75,000 people and a radio audience in the millions. Learn more. Birthday of renowned contralto opera singer Marian Anderson, an important figure in the struggle against racial prejudice. She was at the center of an international news story in 1939, when the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) refused to allow Anderson to sing to an integrated audience in Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C. With the aid of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Anderson performed a critically acclaimed open-air concert on Easter Sunday, April 9, 1939, on the Lincoln Memorial steps in the capital. She sang before an integrated crowd of more than 75,000 people and a radio audience in the millions. Learn more. | |

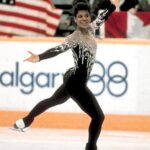

| February 27, 1988 |  Figure skater Debi Thomas takes the bronze medal at the Winter Olympics, becoming the first black athlete to win medal at a Winter Olympics. Thomas was the 1986 World Champion and a two-time US National Champion. Learn more. Figure skater Debi Thomas takes the bronze medal at the Winter Olympics, becoming the first black athlete to win medal at a Winter Olympics. Thomas was the 1986 World Champion and a two-time US National Champion. Learn more. | |

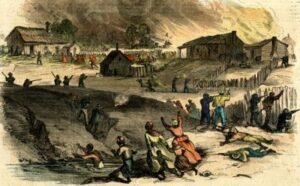

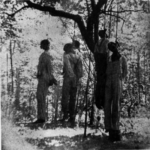

| February 28, 1708 |  One of the first recorded revolts by enslaved people in America erupts in Newton, Long Island, NY, resulting in the deaths of seven white people. Following the rebellion, a Black woman is burned alive and one Native American man and two Black men are hanged. One of the first recorded revolts by enslaved people in America erupts in Newton, Long Island, NY, resulting in the deaths of seven white people. Following the rebellion, a Black woman is burned alive and one Native American man and two Black men are hanged. | |

| February 28, 1895 |  Bluefield Colored Institute is founded in Bluefield, West Virginia, as a “high graded school” for African American youth in the surrounding area. It is known today as Bluefield State College and is a part of West Virginia's public education system. Despite tenuous funding, hostility from the state, and distance from northern cities, the college was heavily involved in the explosion of Black American culture known as the "Harlem Renaissance” of the 1920s and 1930s. Langston Hughes read poetry, John Hope Franklin taught Negro History, and heavyweight champion Joe Louis boxed exhibitions on campus. Fats Waller, Duke Ellington, Dizzie Gillespie, and Count Basie entertained at campus events. Bluefield State's "Big Blue" football team twice won national Negro College Athletic Association championships in the late 1920s. Bluefield was one of the first historically Black colleges/universities (HBCU) to become and remain predominantly white. Learn more. Bluefield Colored Institute is founded in Bluefield, West Virginia, as a “high graded school” for African American youth in the surrounding area. It is known today as Bluefield State College and is a part of West Virginia's public education system. Despite tenuous funding, hostility from the state, and distance from northern cities, the college was heavily involved in the explosion of Black American culture known as the "Harlem Renaissance” of the 1920s and 1930s. Langston Hughes read poetry, John Hope Franklin taught Negro History, and heavyweight champion Joe Louis boxed exhibitions on campus. Fats Waller, Duke Ellington, Dizzie Gillespie, and Count Basie entertained at campus events. Bluefield State's "Big Blue" football team twice won national Negro College Athletic Association championships in the late 1920s. Bluefield was one of the first historically Black colleges/universities (HBCU) to become and remain predominantly white. Learn more. | |

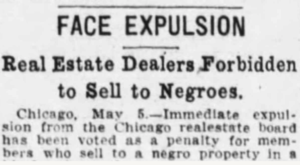

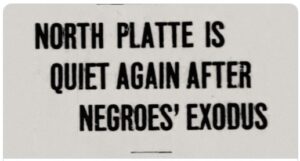

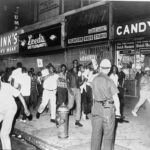

| February 28, 1910 |  After a reported verbal altercation between an unidentifiable African American man and three white men on the evening of February 26, an armed white mob formed and began shooting at and vandalizing the storefronts of the primarily black business district in Eldorado, AR. The violence ended on February 28, upon deployment of the local National Guard unit. Following the violence a significant percentage of Eldorado’s Black population left the area. Learn more. After a reported verbal altercation between an unidentifiable African American man and three white men on the evening of February 26, an armed white mob formed and began shooting at and vandalizing the storefronts of the primarily black business district in Eldorado, AR. The violence ended on February 28, upon deployment of the local National Guard unit. Following the violence a significant percentage of Eldorado’s Black population left the area. Learn more. | |