On Memorial Day we honor and mourn all who gave their lives in service in the United States Armed Forces. Though it is common to celebrate Memorial Day as the start of the summer season with picnics and parades, at its core this holiday is a solemn remembrance of those lost and of the Gold Star families who survived them.

Ridgefield Allies joins with all Americans in remembrance, gratitude, and mourning for those who sacrificed their lives in services to our country and in solidarity with their loved ones and descendants. We urge parents to instruct and instill in their children the solemn reason for this long weekend.

In so remembering, honoring, and mourning, it is critically important that we consciously overcome the popular and misconceived imagery of the fallen as exclusively one archetype of American. The hundreds of thousands who sacrificed their lives in service are the exclusive province of no single subset or population, but rather are the shared loss — and the shared obligation to remember and honor — of all Americans: people of all races, colors, creeds, religions, ethnic/geographic origins, sexual orientations, genders, gender identities/expressions. This is not to diminish the contributions and sacrifices of members of any one American identity, but rather to recognize the contributions and sacrifices of members of every American identity.

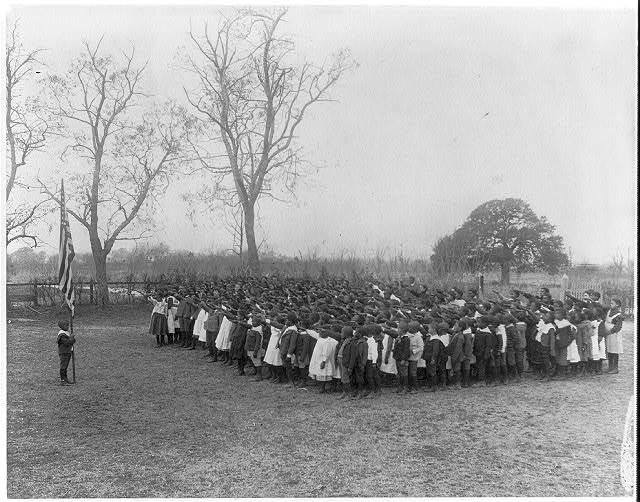

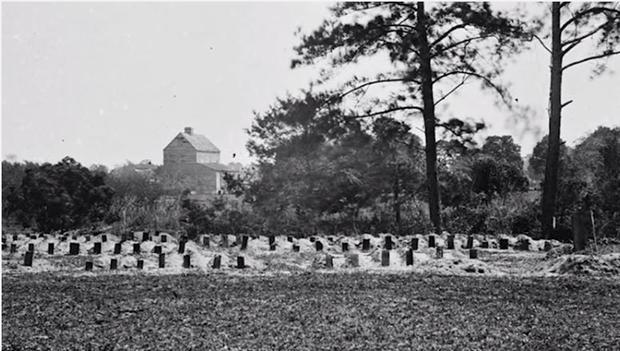

It also behooves us to be aware that one of the most direct early American precedents to our modern Memorial Day observance was established by over 10,000 formerly enslaved African Americans on May 1, 1865. The recently emancipated African Americans marched onto the former Washington Race Course in Charleston, South Carolina, which the Confederacy had turned into a prison camp, in order to commemorate the hundreds of Union soldiers who had died on those grounds. The African Americans had worked in the previous weeks burying the bodies of the soldiers. They had cleaned up the grounds while creating an enclosure and an arch that read “Martyrs of the Race Course”. The day, which was called “Decoration Day,” was attended by the Freedmen, teachers, missionaries and members of the National Print Press. The marchers brought flowers, sang songs, prayed, listened to sermons and later had picnics. Similar memorial observances by communities of all colors and creeds, both formal and informal, followed. Here again, we are reminded that Memorial Day is the province of no single subset of Americans, but of all Americans.